Monastic robes date back to the time of the Buddha over 2,600 years ago. The robes are a mark of identity, clearly distinguishing members of a monastic community from lay people. The disciplinary texts for monks and nuns contain many guidelines on robes.

Originally, the robe was just one rectangular piece of cloth carefully wrapped. Over time, each Buddhist tradition has developed its own set of rules and robes and settled on a color.

A young Tibetan Buddhist nun learns how to wear monastic robes. Photo by Olivier Adam

The Different Colors of Monastic Robes

The original rules about monastic robes are recorded in the Vinaya Pitaka of the Pali Canon and these include rules about color. The Pali Canon says the robes of fully ordained monks, may be dyed “tinting them red using the bark of the bāla tree, or using saffron, madder, vermillion, āmalakī, ocher, orpiment, realgar, or bandujīva flowers.” It is also said that the robes should be made using a dye that was readily available, not something expensive or special.

These natural dyes, created from various plants, minerals, and spices such as saffron gave the cloth used in southeast Asia a yellow-orange color. Hence the term “saffron robes”. The Theravada monks of southeast Asia still wear these spice-color robes today, in bright orange as well as shades of curry, cumin, and paprika.

The colors of Buddhist monastic robes vary depending on the tradition and on what was readily available. Also, the color of female monastics robes sometimes differs from that of male monastics, even in a shared tradition.

In Thailand, monks wear orange and saffron robes and nuns wear white robes. In Japan, monks’ and nuns’ robes are traditionally black, grey, or blue. In Korea, robes are black, brown, or gray. In Tibet and in the Tibetan diaspora, both monks and nuns wear maroon or burgundy red robes.

These charming monk and nun dolls are handmade by the nuns at Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute. The dolls’ robes are made from recycled nuns’ robes. Each doll has its own mini mala, a set of prayer beads. We sell them in our online store to help the Tibetan Buddhist nunneries.

Of the various Buddhist traditions, Tibetan Buddhism has perhaps one of the more complex variety of robes. Although the main color of Tibetan robes is burgundy, the historical yellow of monastic robes is still present in both nuns’ and monks’ robes.

Cloth for Monastic Robes

The cloth and sewing pattern of monastic robes has ancient symbolism. Like the wandering holy men at the time of the Buddha, the first monastics wore a robe stitched together from rags.

The Buddha instructed the first monks and nuns to make their robes of “pure” cloth, meaning cloth that no one wanted. They scavenged in rubbish heaps and cremation grounds for discarded cloth and cut away any unusable bits before stitching the pieces together to form three rectangular sections of cloth. The humble nature of the cloth itself represented detachment from the physical world in pursuit of enlightenment.

Vinaya texts insist that robes should be clean at all times and should be dried in the open air. This, of course, is a challenge during the monsoon. Photo from Tilokpur Nunnery courtesy of Olivier Adam.

Tibetan Monastic Robes

Geography and climate have shaped the evolution of monastic robes. The Buddha is usually depicted wearing a simple robe draped over his body, often leaving his right shoulder bare. This style of robes is still found in the Theravada Buddhist tradition. Early Buddhist robes were meant for hot climates and were not warm enough for Tibet’s cold, high-altitude conditions. Hence, an upper and an outer garment are part of monastic robes in Tibetan Buddhism.

Early Buddhist robes were meant for hot climates and were not warm enough for Tibet’s cold, high-altitude conditions. An elderly nun saying the Tara Puja at Geden Choeling Nunnery, Dharamsala. Photo by Olivier Adam

The Tibetan word for robes is ཆོས་གོས་ [pronounced: chos gö], meaning “religious clothing,”. A basic set of robes for a Tibetan Buddhist monastic consists of these parts:

The dhonka, a shirt with cap sleeves. This shirt was added to Tibetan monastic robes in the 14th century, at the time of Tsong Khapa. Because of the cold Tibetan climate, it was felt that the monks needed an upper robe. The dhonka is maroon or maroon and yellow with blue piping. The blue piping has historic symbolism, remembering a period in Tibetan history when Buddhism was almost wiped out. There were not enough monks remaining to bestow ordination, but with the help of two Chinese monks, who always wore some blue garments, they were able to do so. In memory of that help, the blue sleeve edging was made a part of the upper garment.

The shemdap is a maroon skirt made with patched cloth and a varying number of pleats. This is the transformation of the original monastic robe of the Theravada tradition. Monks and nuns no longer wear discarded cloth, but wear robes made from cloth that is donated or purchased. And nowadays the lower robe of Tibetan monastics is simply sewn to look patched.

The chogyu is yellow and worn for certain ceremonies and teachings. Similar to the Theravada robe, it is made of many pieces.

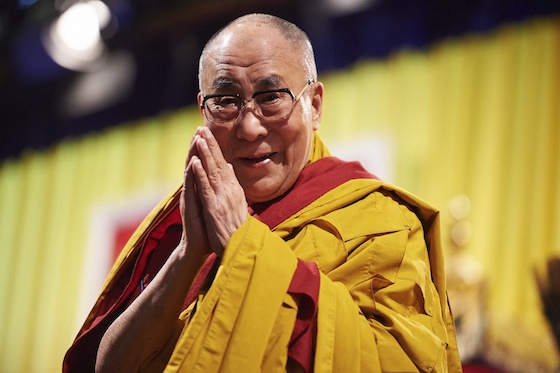

Tibetan lineages wear a maroon color upper robe ordinarily, but generally wear a yellow robe during confession ceremonies and teachings. Photo of His Holiness the Dalai Lama courtesy of Olivier Adam

A maroon zen is similar to the chogyu and is for ordinary day-to-day wear.

The namjar is larger than the chogyu, with more patches, and it is yellow and often made of silk. It is for formal ceremonial occasions and is worn leaving the right arm bare.

A dagam is a heavy woollen cape that monastics wrap around themselves when sitting for long periods of time doing meditation or ritual during cold weather.

The tailoring program at Dolma Ling Nunnery had a modest start with a plan to make nuns robes so that the nuns wouldn’t have to go to the market and pay for the service. Now the tailoring program has expanded greatly and is quite successful. In addition to making robes, the nuns make item for sale in our online store including prayer flags, nun and monk dolls, bags, and Tibetan door curtains.