This special blog post by Julie Brittain has news and archival photos of Dolma Ling Nunnery in 1993 when the nunnery was being built. Julie, now a long-time supporter of the Tibetan Nuns Project, wrote it in 1993 as part of a series of short reports for CBC, the Canadian Broadcasting Corporation. This is a report she wrote about her time at Dolma Ling and describes her time with the nuns as the nunnery was being built.

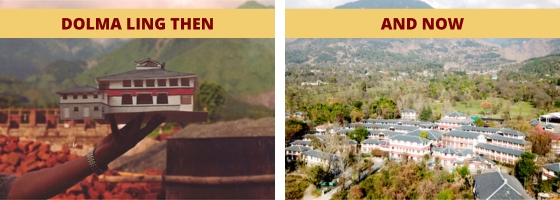

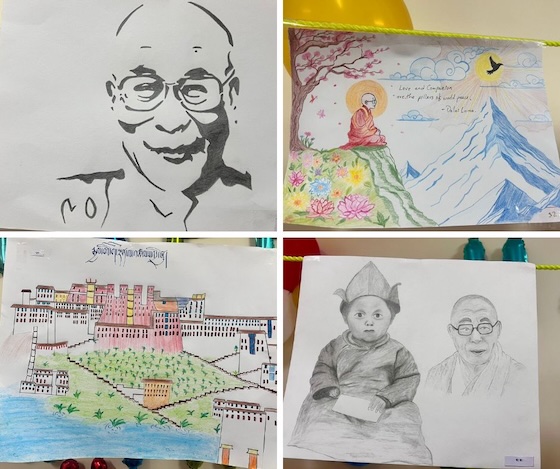

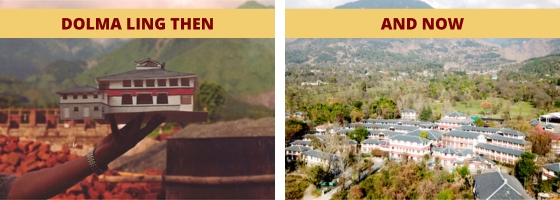

On the left, a nun holds a paper model of Dolma Ling. December 8, 2025 is the 20th anniversary of the inauguration of Dolma Ling by His Holiness the Dalai Lama. The nunnery took 12 years to build. Our current project is to build special housing for elder nuns.

Background to Julie’s Letters from Dharamsala 1993

In 1993, when I was in Dharamsala, I was writing 3-minute “letters” to be read out on a CBC Radio Show from St. John’s Newfoundland called “On The Go”.

I first visited Dharamsala in 1988, arriving directly from Lhasa, where I’d worked for a year at Tibet University. I’d been a couple times more to Dharamsala between 1988 and 1993, but this was the longest stay.

Julie Brittain at Dolma Ling Nunnery near Dharamsala in 1993.

I wrote 20 letters for “On The Go”. CBC Radio didn’t air them all and I was told they didn’t air the two I wrote about Dolma Ling. I guess some were just a bit outside of the listeners’ experience.

Letter from Dolma Ling Nunnery

There’s an understanding in Dharamsala that western visitors should make a contribution to the refugee community while they are part of it. There’s no shortage of worthwhile projects which can use some extra help. One afternoon I ran into Betsy Napper, whom I’d met briefly in Lhasa in 1987. [Elizabeth (Betsy) Napper, PhD, is the US Founder and Board Chair of the Tibetan Nuns Project.]

She told me about an organization called the Tibetan Nuns’ Project. She was co-director. It was set up in 1987 to receive nuns fleeing into exile from Tibet. There were over 100 such nuns in the community now and the Tibetan Nuns’ Project had founded a nunnery, Dolma Ling, to accommodate and care for some of them, eventually, all of them. They could use my help organizing their English teaching programme.

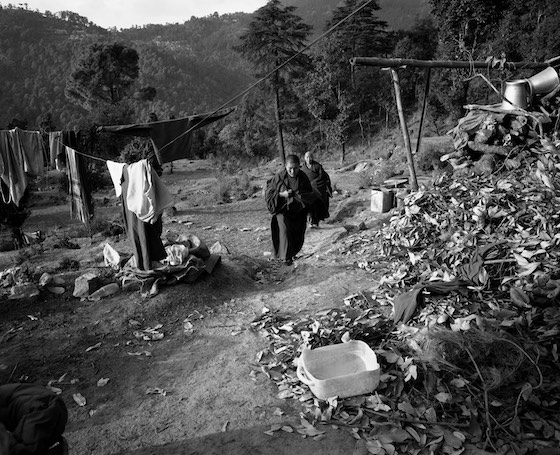

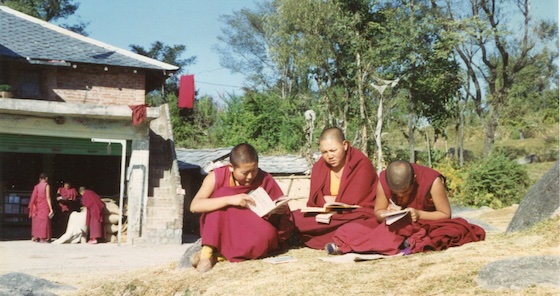

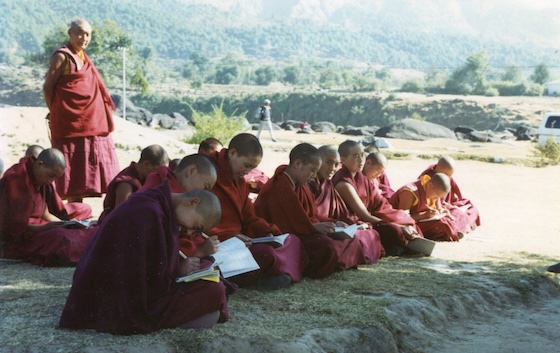

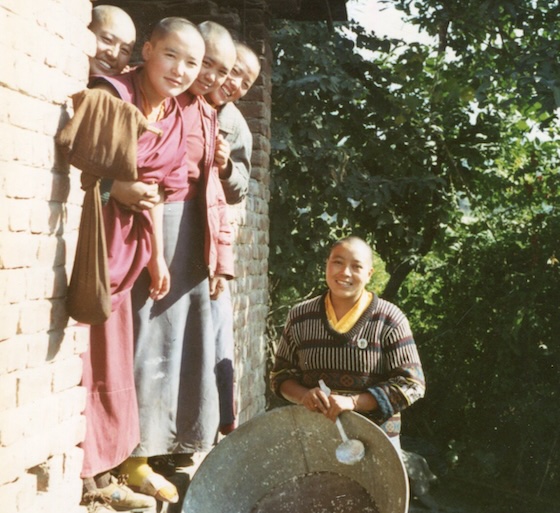

The Tibetan Nuns Project was founded in 1987 in response to wave of nuns escaping from Tibet to India. They had walked over the Himalayas and were ill and exhausted. Many of them had been imprisoned and tortured for taking part in peaceful demonstrations calling for basic human rights. Photo by Julie Brittain, 1993.

I’d heard about the Nuns Project. I knew that some of the nuns had served time in prison in Tibet, for taking part in pro-independence demonstrations, or just for simply being nuns. Many of them had been thrown out of their nunneries by the authorities. They came to India, often on foot as far as Nepal, just so that they could carry on their practice as nuns.

The nuns escaped into exile seeking freedom to practice their religion, culture, and language. The nuns arrived in northern India to a refugee community already struggling to survive. The two existing Tibetan Buddhist nunneries were already overcrowded. Photo by Julie Brittain, 1993.

While I lived in Lhasa, I’d visited many of the nunneries, in the city and further afield. A few in the Lhasa area I’d visit on a regular basis. I heard the nuns’ stories first hand over the year I was there, as we’d talk over the bottomless bowls of butter tea they’d serve me. I admired the courage and conviction that had brought these women on such a dangerous journey, into exile, and I decided this would be my contribution to the refugee community. If I could, I’d return a little of the warm hospitality and friendship they’d shown me in Tibet, where I myself frequently felt alone and confused by life at Tibet University, where I was far from welcome as a foreigner.

Photo from 2025 of Geshema Delek Wangmo, the principal of Dolma Ling, showing Sikyong Penpa Tsering, the political leader of the Central Tibetan Administration, the foundations for the housing for elder nuns. Photo tibet.net

The half hour drive down to Dolma Ling Nunnery is spectacular, as is the setting of the nunnery itself. To the north, mountains shoot up dramatically from the valley floor. Clear mountain streams bubble around the big grey glacial boulders.

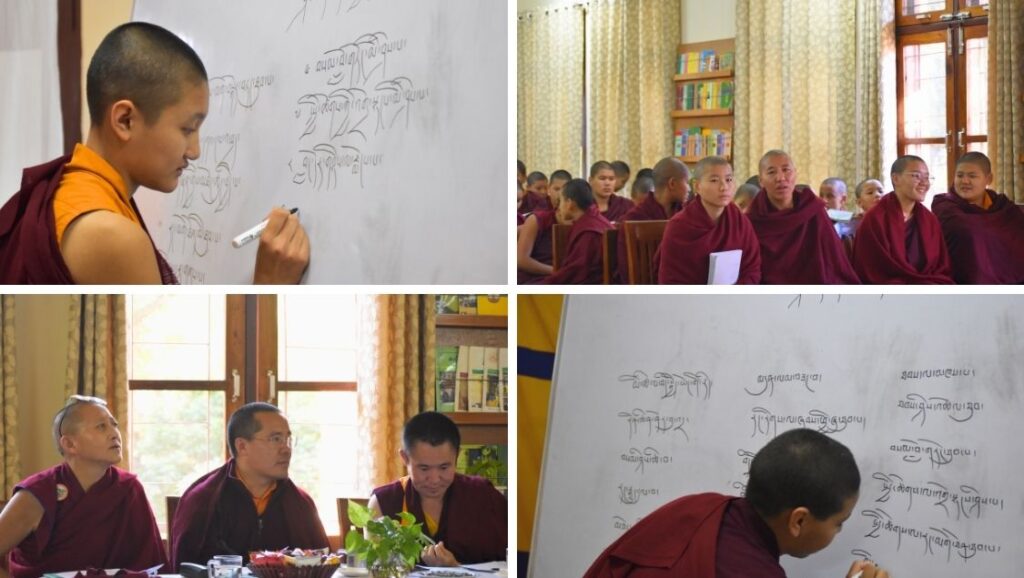

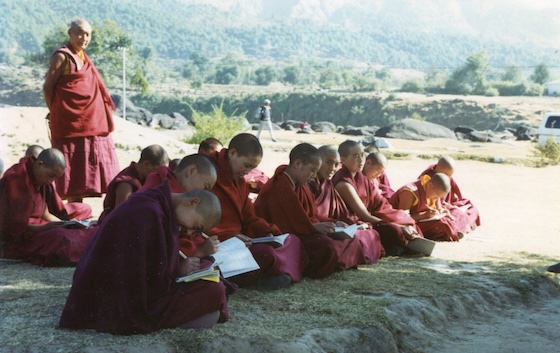

Most refugee nuns escaping to Northern India had no education in their own language, nor had they been allowed education in their religious heritage while in Tibet. Many were illiterate on arrival and could not even write their own names.

Goats, sheep, cows, buffalo, donkeys and horses belonging to neighbouring farms crop the lush grass to a soft green carpet so that the valley looks like a big park.

Right now, Dolma Ling is spread out and make-shift. The nuns live in four rented houses. There are as many bunk beds in each room as will fit.

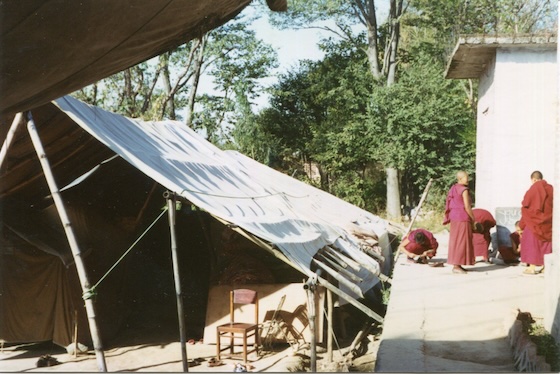

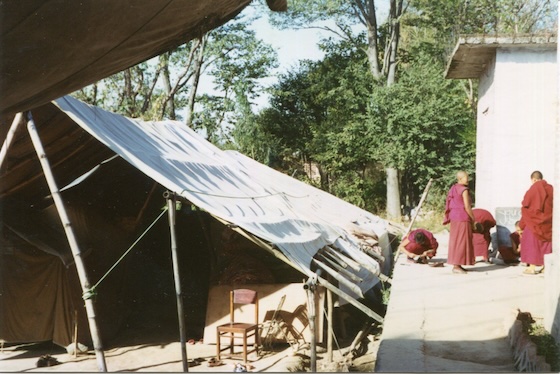

Their classroom and gompa is a doorless building which has a dirt floor, mud-washed walls and a polythene tent roof.

Only in the visitors’ room is there a little space, a carpet and chairs to sit on. This is also where the nunnery valuables are kept – religious books, two sewing machines and the accounts books.

The nuns take off their shoes when they go into this room. Just across the field what will one day be the real Dolma Ling is underway. This is a large complex which will have dormitories for 200 nuns, classrooms, a small hospital, and a gompa. The nuns work on the site in the mornings and evenings, helping the labourers with tasks like carrying bricks.

Construction of Dolma Ling began in 1990 and the major parts of the nunnery were completed in 2005. The nuns themselves took part in the construction of the nunnery, laboring to carry bricks and mortar, and dig the foundations. Photo by Jessica Tampas.

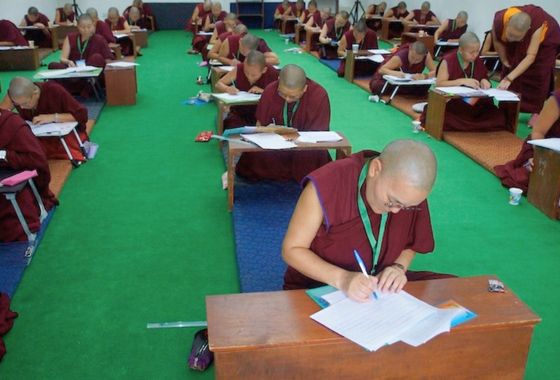

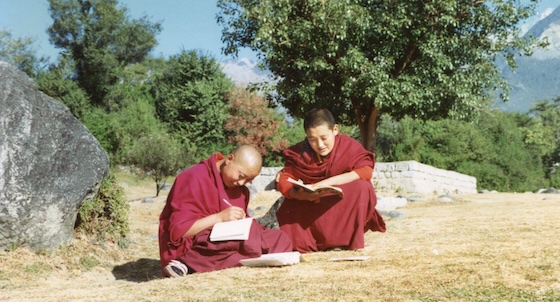

I’ve taught English in a lot of different countries, but the first time I met the nuns was like starting out all over again. Before me, sitting cross-legged on the floor, three rows of shaven-headed ladies aged between about 16 and 35. They all wore identical yellow silk vests and maroon robes. I had no text books, or rather none that were relevant for a Tibetan nun newly arrived in India.

I asked them to tell me about their daily schedule. They get up at 4:30 and pray until 6:30. Then they have breakfast. After that, the whole day is crammed with classes, religious practices and building work. After their evening meal, they spend five or six hours learning scriptures by heart, often not getting to bed before midnight.

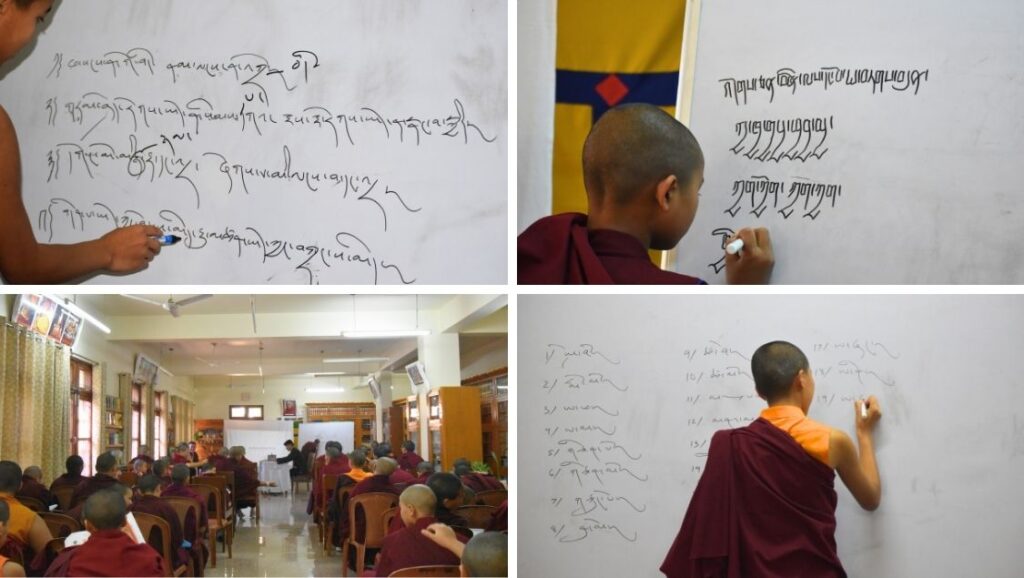

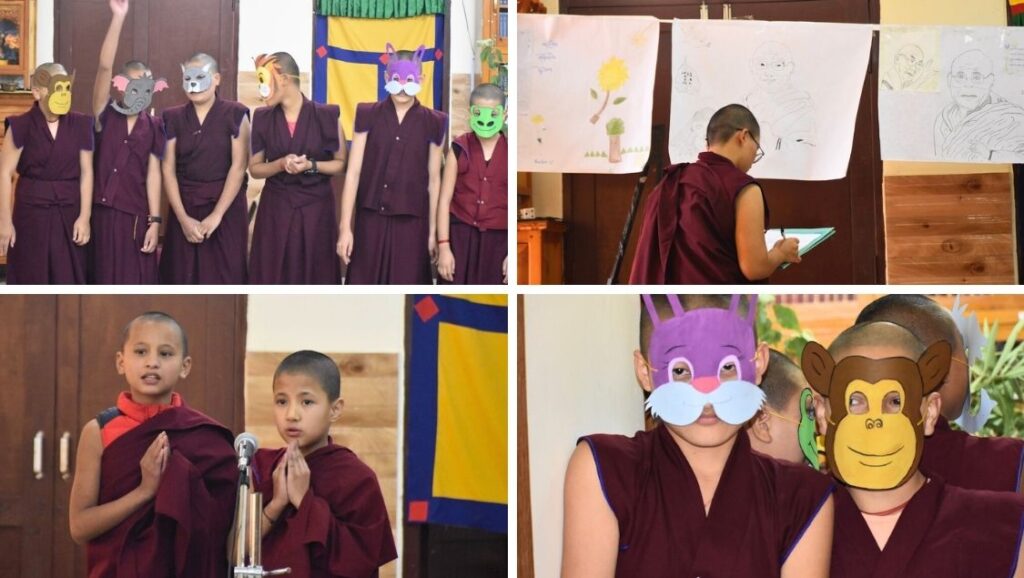

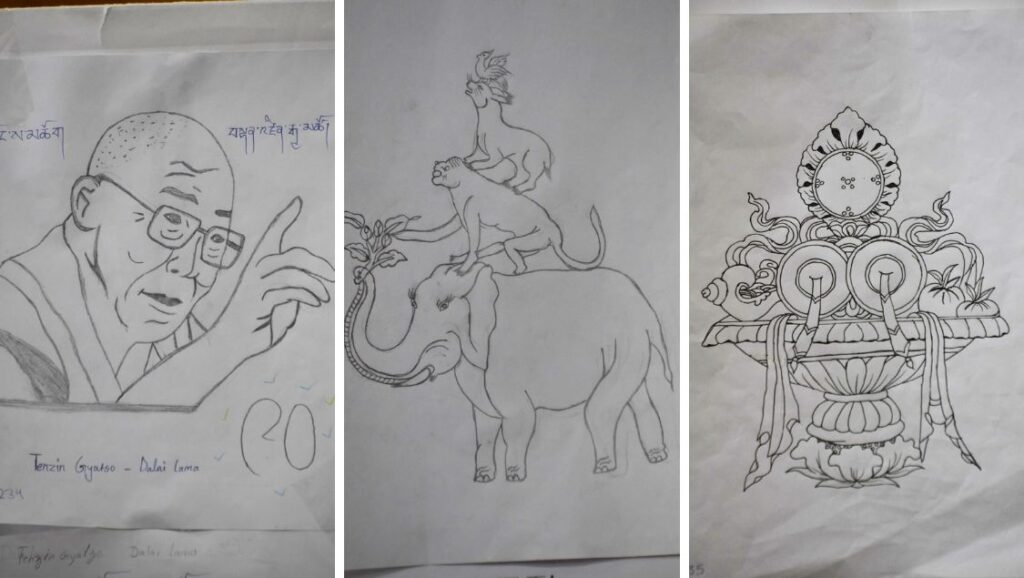

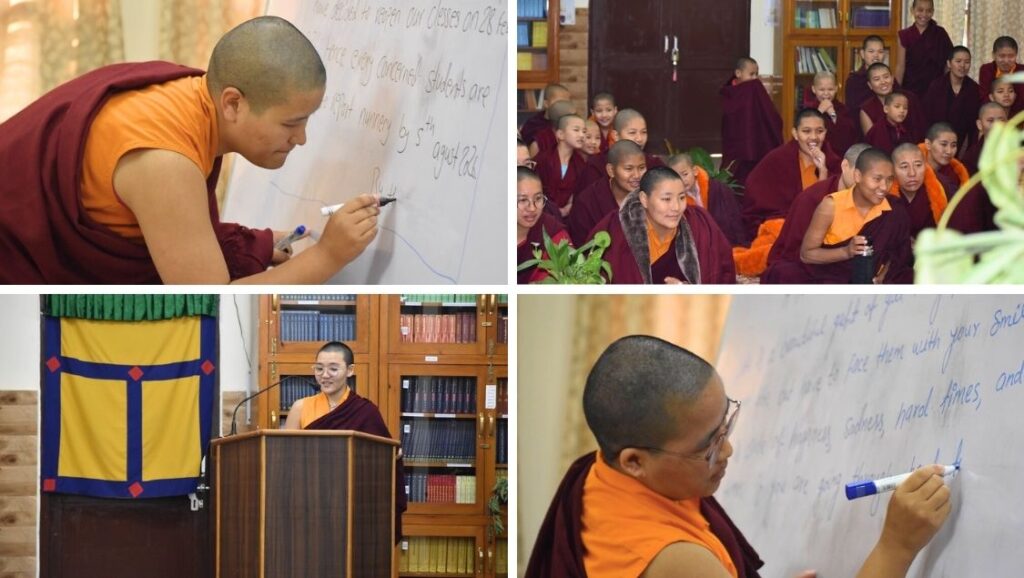

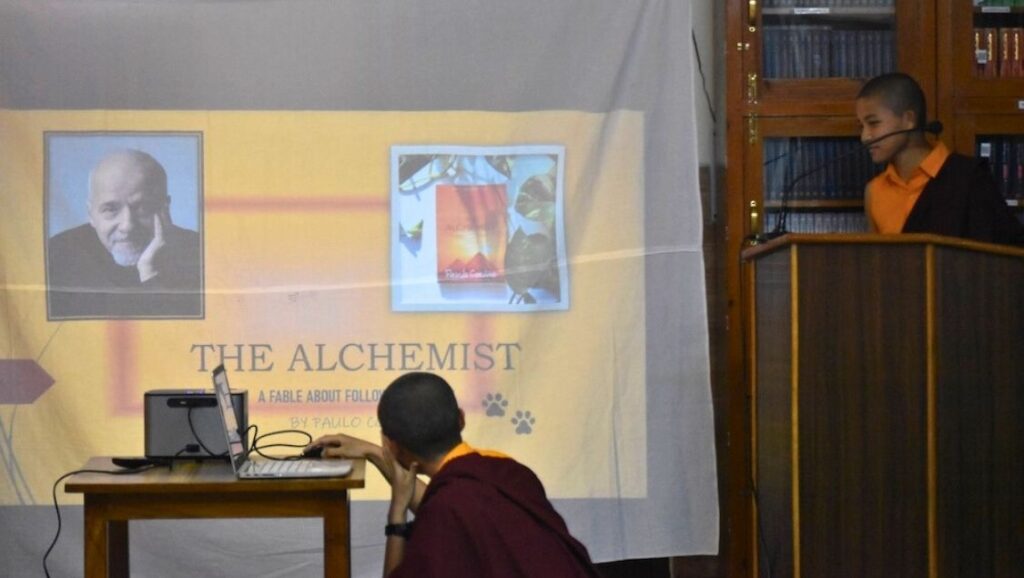

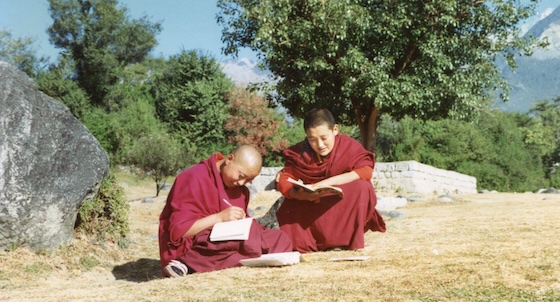

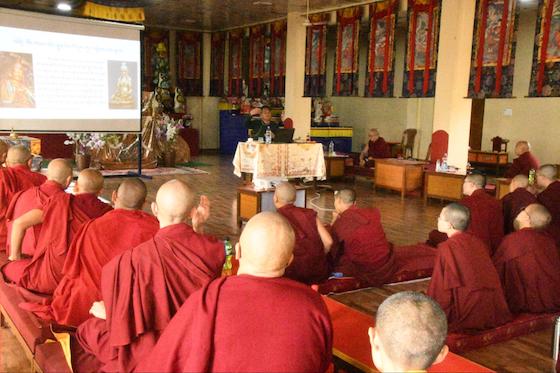

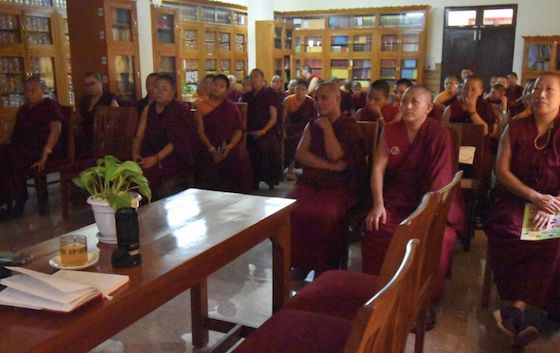

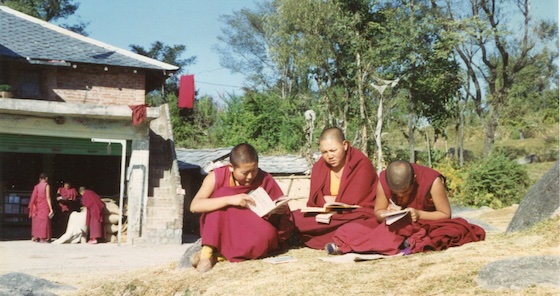

Dolma Ling Nunnery was successfully completed after 12 years of hard work. Now home to about 300 nuns, it offers a 17-year curriculum of traditional Buddhist philosophy and debate, as well as modern courses in Tibetan language, English, basic mathematics, and computer skills. Photo by Julie Brittain, 1993.

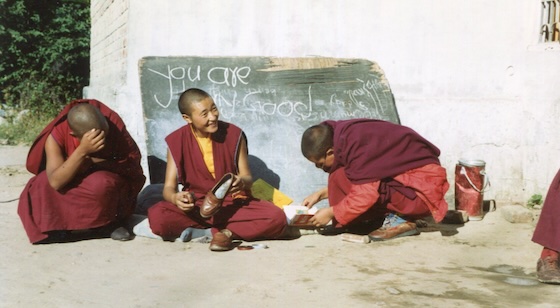

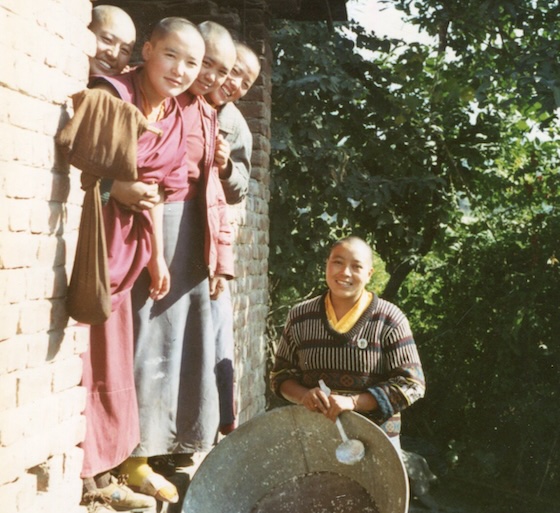

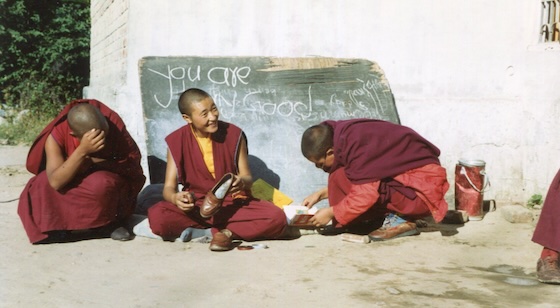

I couldn’t believe anyone could survive such a life. ‘Don’t you get tired? How can you live that way!’ I asked. They laughed at me, part-hiding their faces in a corner of robe or on a friend’s shoulder. This was the life they loved, the life they’d crossed the Himalayas to pursue. For them the question was how to live any other way.

During the week the Dolma Ling nuns have a tight schedule. If you want to see one of them at leisure, you have to do it on a weekend. I dropped in one Saturday after lunch to visit a 26 year old nun I’ll call Pema – it’s not her real name – who arrived in India this summer. I wanted to hear her story because it’s typical of many Tibetan monks and nuns these days. This piece is broadcast with her permission on the understanding I do not use her real name.

One Nun’s Story

Pema was in prison in Lhasa for three years, from 1989 to 1992. She was one of 20 nuns and three monks arrested for taking part in a small pro-independence demonstration outside a cultural event put on by the authorities. This happened while Lhasa was under martial law in the fall of 1989, in the grounds of the Norbulingka, the Dalai Lama’s Summer Palace. They shouted ‘Free Tibet’ and ‘Long live the Dalai Lama’. They were all sentenced without trial.

During her time in prison Pema was tortured and beaten. Beatings to the head have left her blind in her left eye and suffering from headaches. She was in pain the day I met her. As she spoke to me through an interpreter, she held the palm of her hand against the left side of her face, which seemed swollen.

Early classroom. “The nuns, when they first came via Nepal to India, were in very poor physical shape and of course they had nothing – from 1987 onwards. They were traumatised and physically battered,” said Rinchen Rinchen Khando Choegyal, Founding Director of TNP. Photo by Julie Brittain, 1993.

Pema comes from a village west of Lhasa. Her family are farmers. She has two older siblings, both of whom are also farmers. At the age of 21 she decided to become a nun. As she put it, by doing this she would ‘bring benefit to all sentient beings’. In 1987 she joined a nunnery not far from Lhasa. I’d visited two or three times in 1987 on horseback – during martial law, travelling by horse was one of the few ways to get around and not have someone from the Public Security Bureau follow to see who you were talking to.

I asked her how she’d got out of Tibet. She told me that she’d walked from Lhasa, south to the Nepali border, in a party of 16 Tibetans. To avoid being spotted by the Chinese troops who patrol all the main roads across Tibet, they walked at night and hid in caves during the day. They were leaving Tibet illegally and would have been arrested if they’d been caught. Their journey lasted 19 days and took them around Mount Everest.

Why, I asked, had she taken part in demonstrations. She knew how dangerous it was. She knew she would be arrested, and most likely tortured and imprisoned. She replied, ‘To obtain freedom for the Tibetan people.’ I wanted to know if she felt it was her duty as a nun to demonstrate. No, she said, it wasn’t her duty. Conviction had made her do it. Monks and nuns in general have a lot of conviction, she told me.

Building Dolma Ling Nunnery. Photo by Julie Brittain 1993.

While she was in prison she worked six days a week, from nine to five, digging fields. The food was poor and there was never enough of it. There was no meat. Vegetables, served once a day, were often full of maggots. Otherwise, they lived on black tea and steamed bread. She said that even when relatives brought prisoners nutritious food, it was often confiscated by the guards.

Tibetan Buddhist nuns sewing in 1993. Today, there is a tailoring section at the nunnery that makes robes and also many items for sale in our online store such as prayer flags, Tibetan door hangings, bags, and dolls.

Why had she come to India, I asked. She told me she wanted to continue her studies, something she couldn’t do in Tibet. Everyone at her nunnery had been refused a renewal of the papers they needed to be there officially. A condition of her release from prison, in any case, had been that she wasn’t allowed to rejoin her nunnery. The only way for her to continue being a nun was to go into exile. If she tries to return, she said, she’ll be arrested again.

An anonymous Tibetan poet has paid tribute to Pema and the others who were arrested at the Norbulingka that day, in a resistance song that circulated in Lhasa in 1989. In translation the song goes like this:

In the Norbulingka

Many different flowers have bloomed

Neither hailstorm nor winter frost

Will untie our unity

We stand up to leave. Pema places the palms of her hands together and bows to us in the traditional Tibetan way. We wish her happiness in India.

One of our goals now is to put our core programs on more solid ground with our Long-Term Stability Fund launched about 30 years after this photo was taken. Photo by Julie Brittain, 1993.

Current Needs

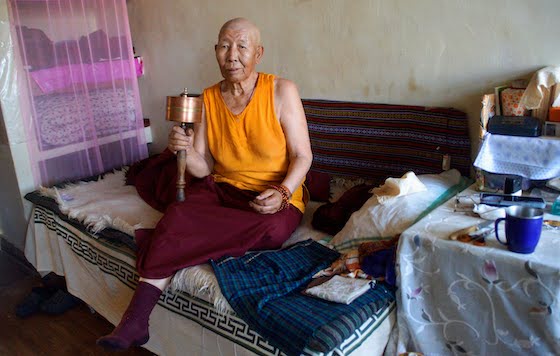

It is now over 30 years since Julie wrote this letter for CBC Radio. The Tibetan Nuns Project is now working on two major projects to help the nuns. The first is our Long-Term Stability Fund to put more of our core programs on solid ground. The second is to build Housing for Elder Nuns at Dolma Ling.

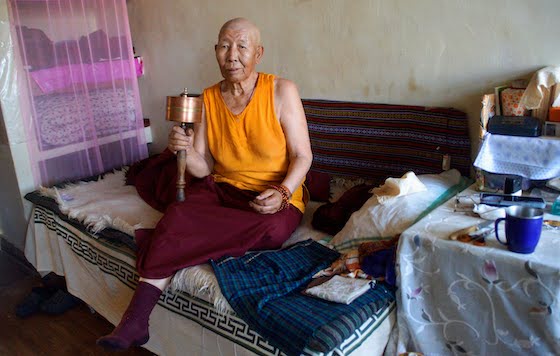

Ani Rigzen, aged 74, is one of the elder nuns at Dolma Ling. She said, “I escaped Tibet after torture took everything from me, my family, my home, my culture. Even now, with failing eyesight and constant pain, I carry those scars. Dolma Ling is my only family, the only home I have left. With your support, a senior home here would mean I could spend my last years with dignity and peace, surrounded by my sisters. This would be the greatest gift of my life.”

Dolma Ling Now

December 8, 2025 marks the 20th anniversary of the inauguration of Dolma Ling by His Holiness the Dalai Lama.

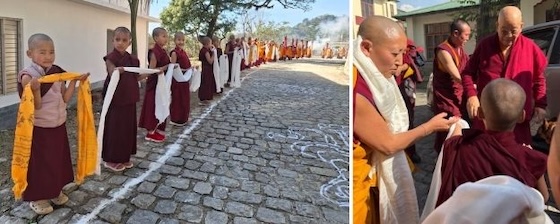

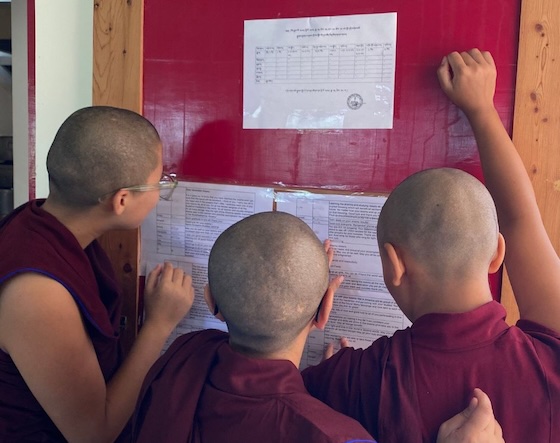

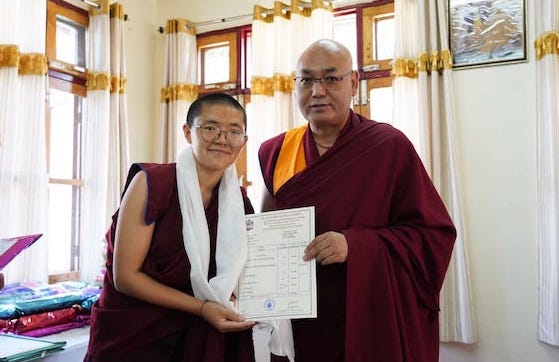

In April 2025, the nuns celebrated big changes in the leadership at Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute. For the first time since the nunnery was inaugurated 20 years ago, Dolma Ling transitioned from having a male principal to leadership by the nuns themselves.

You can learn more about life at Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute with these slideshows and this blog post about daily life and the nuns’ curriculum.

Thank you so much for your support!