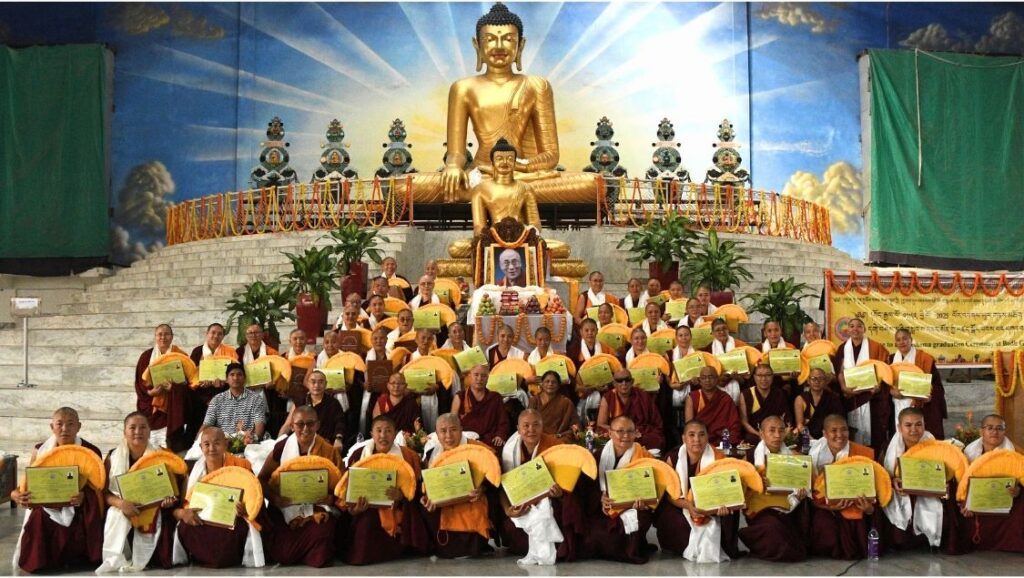

On November 6th, 47 Tibetan Buddhist nuns graduated as Geshemas in the holy city of Bodh Gaya. The Geshema degree is the highest academic degree in the Gelug tradition and was only opened to women in 2012. This is the largest group of Geshema graduates since the first Geshema graduation took place in 2016, bringing the total number of Geshemas to 120.

Congratulations to the 47 Tibetan Buddhist nuns who graduated in November 2025 as Geshemas.

In this blog post, we share photos taken by the Dolma Ling Media Nuns of the special event and news of the annual inter-nunnery debate, the Jang Gonchoe, which started 30 years ago in 1995.

Record Number of Nuns Earn Geshema Degrees

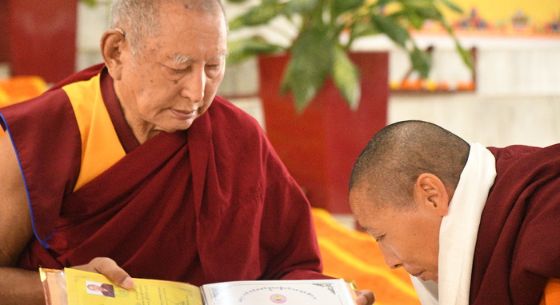

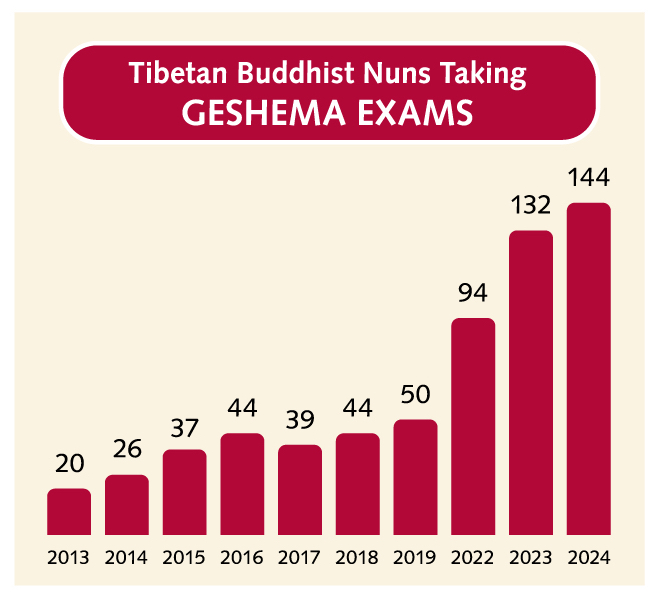

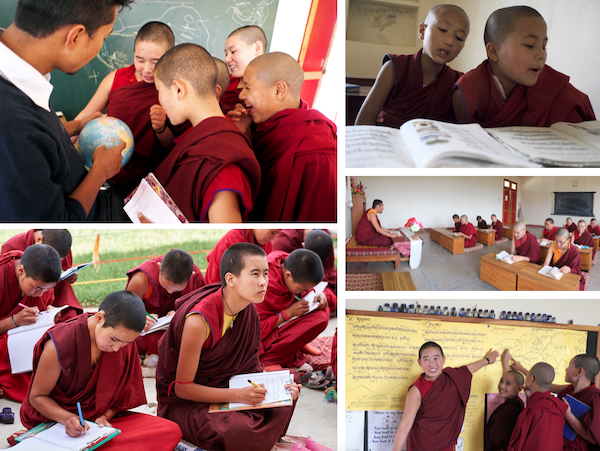

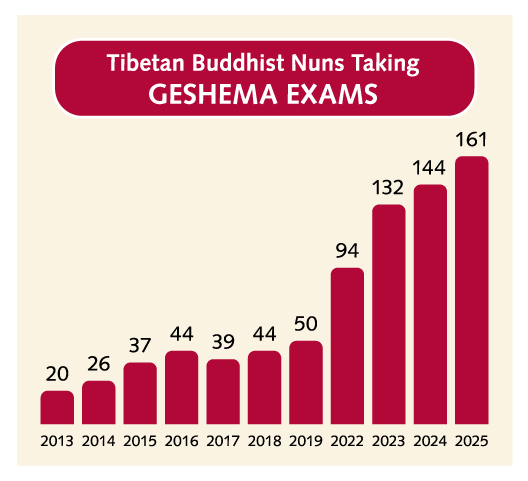

In the summer of 2025, a record number of nuns took various levels of exams for the Geshema degree, equivalent to a PhD in Tibetan Buddhist philosophy. The rigorous written and oral are completed over four years, with one set held each year. To be eligible to take their Geshema exams, the nuns must first complete at least 17 years of study.

A collage showing parts of the Geshema graduation ceremony in November 2025. Elements include an oath-taking ceremony and a special debate event, followed by a traditional khata (scarf) offering ceremony.

The Geshemas are paving the way for other nuns to follow in their footsteps. The momentum is building. Not long ago, this increased status of nuns was almost unimaginable. We are so grateful for your support to educate and empower these dedicated women!

2025 marks another new record for nuns taking various levels of the 4-year Geshema exams. The degree was only opened to women in 2012. No exams were held in 2020 or 2021 due to COVID.

The exams were hosted this year by Dolma Ling Nunnery and Institute near Dharamsala from July 21 to August 16, 2025. The costs of the nuns’ travel, food, and the exam process were once again covered by the Tibetan Nuns Project’s Geshema Endowment Fund.

In November, the Jang Gonchoe closing ceremony and Geshema certification were held on the same day, attended by chief guests Dr. Mahashweta Maharathi, Secretary of the Bodh Gaya Temple Management Committee and Gen Tenzin la from Namgyal Monastery in Dharamsala.

Here’s a list of the Geshema graduations since the formal approval in 2012:

- 2016: 20 nuns became Geshemas

- 2017: 6 nuns graduated as Geshemas

- 2018: 10 nuns became Geshemas

- 2019: 7 nuns graduated at the end of November

- 2020: exams cancelled due to the pandemic

- 2021: exams cancelled due to the pandemic

- 2022: 10 nuns became Geshemas

- 2023: 7 nuns graduated

- 2024: 13 nuns graduated as Geshemas at the 7th convocation ceremony

- 2025: 47 nuns graduated as Geshemas in Bodh Gaya

The Annual Inter-Nunnery Debate

From October 5th to November 8th, 460 nuns and 23 teachers from 10 Tibetan Buddhist nunneries in India and Nepal gathered in Bodh Gaya for one month of intensive training in monastic debate.

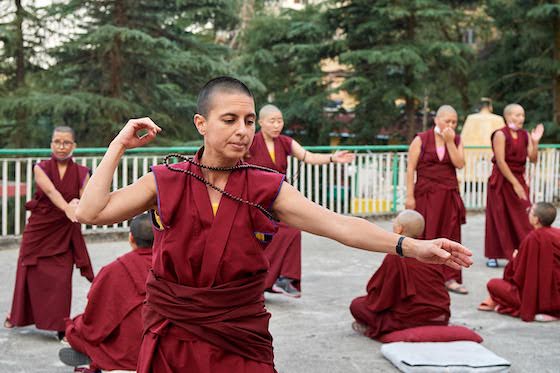

Tibetan Buddhist nuns from India and Nepal practice debating at the Mahabodhi Temple (literally the “Great Awakening Temple”) in Bodh Gaya, marking the location where the Buddha attained enlightenment.

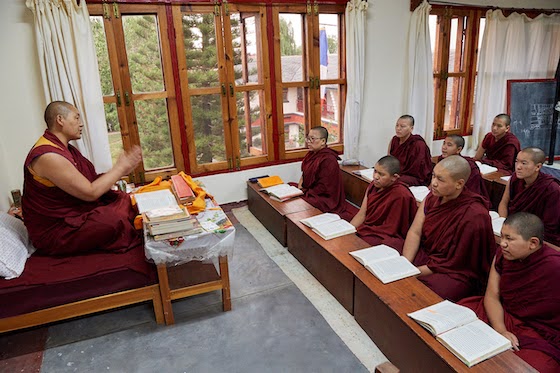

Monastic debate is of critical importance in traditional Tibetan Buddhist learning. Through debate, nuns test and consolidate their classroom learning.

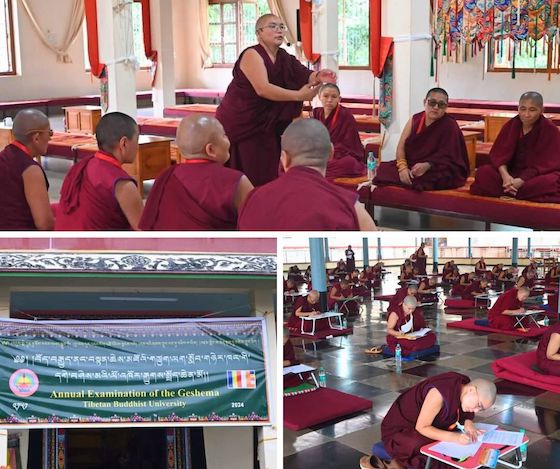

A teacher guides Tibetan Buddhist nuns during their month-long intensive training in monastic debate in Bodh Gaya. 2025 marks the 30th anniversary of the start of the Jang Gonchoe for nuns in 1995.

Although the nuns practice debate daily at their nunneries, the annual Jang Gonchoe debate event provides essential training and practice that is vital for those who wish to pursue higher degrees. The nuns are very grateful to the Kagyu Monlam Office for lending the space since 2019 to the nunneries during Jang Gonchoe and for their continued support.

At the Jang Gonchoe, the nuns take part in structured debate sessions with individual and class-wide debates, followed by an evening inter-nunnery session where two nuns answer questions from a team from another nunnery. Debate strengthens reasoning skills, confidence, and understanding of Buddhist studies.

The inter-nunnery debate helps bring the nuns closer to equality with the monks in terms of learning opportunities and advancement along the spiritual path.

This year, nuns from these 10 nunneries participated:

1. Geden Choeling: 3 teachers + 64 nuns = 67

2. Jamyang Choeling: 2 teachers + 37 nuns = 39

3. Dolma Ling: 3 teachers + 92 nuns = 95

4. Jangchub Choeling: 4 teachers + 77 nuns = 81

5. Kachoe Gakyil Ling: 4 teachers + 64 nuns = 68

6. Thukche Choeling: 2 teachers + 32 nuns = 34

7. Jangsemling: 1 teacher + 17 nuns = 18

8. Jampa Choeling – 1 teacher + 11 nuns = 12

9. Yangchen Choeling : 1 teacher + 26 nuns = 27

10. Sherab Choeling: 2 teachers + 39 nuns = 41

Nuns practice monastic debate in pairs and groups during the month-long Jang Gonchoe. The nuns expressed appreciation to the Kagyu Monlam Office for lending the space in Bodh Gaya for the Jang Gonchoe since 2019 and for their continued support.

1995-2025: The 30th Anniversary of the Inter-Nunnery Debate

The Jang Gonchoe for nuns was first initiated in 1995, making this year its 30th anniversary, though there was a year-long gap during the Covid pandemic when the event could not take place. Because of that missed year, the nuns’ committee has decided to count this as the 29th Jang Gonchoe instead of the 30th.

The inter-nunnery debate has been supported since 1997 by the Tibetan Nuns Project through our Jang Gonchoe Endowment Fund. Now we want to put more of our core programs on a sustainable footing with our Long-Term Stability Fund.

Before 1995, there was no Jang Gonchoe for nuns and this learning opportunity was only open to monks. The Tibetan Nuns Project, with the wonderful support of His Holiness the Dalai Lama, played a critical role in opening up this learning opportunity to women. Establishing a comparable debate session for nuns has been an integral part of the nuns reaching their current level of excellence in their studies.

The inter-nunnery debate has been supported since 1997 by the Tibetan Nuns Project. Our Jang Gonchoe Endowment Fund covers costs such as transportation, food, and accommodation for the nuns and teachers who wish to attend.

The following video is a great primer on Tibetan Buddhist debate by nuns. It’s taken from a longer video made by the nuns at Dolma Ling Nunnery in northern India. It answers many of the frequently asked questions about Tibetan Buddhist debate, such as the meaning of the hand movements.

Can’t see the video? Click here.

Nuns Learning Tibetan Buddhist Debate

“It all happened because of the kindness, generosity, and genuine concern shown by all the wonderful donors who supported us for so many years,” said Rinchen Khando Choegyal, Founding Director and Special Advisor to the Tibetan Nuns Project, in a past interview.

“Much as we had the blessings from His Holiness the Dalai Lama and the vision, determination, and courage to pursue this matter to the full, without their generosity we would not have been able to have the Jang Gonchoe every year, which was and is the moving force behind every step of progress in education the nuns have made,” she said.

In 2025, 460 nuns from ten nunneries took part in the annual inter-nunnery debate, the Jang Gonchoe. The event began in 1995. Prior to that, nuns did not have this opportunity.

His Holiness the Dalai Lama has often spoken of the need to examine the teachings of the Buddha closely and with an inquisitive mind. “This is the 21st century and we need to understand the Buddha’s teachings in the light of reason. When we teach, we need to do so on the basis of reason,” His Holiness the Dalai Lama told the nuns at the end of the 2014 Jang Gonchoe.

His Holiness added, “Nowadays, the Nalanda tradition of approaching the Buddha’s teachings with logic and reason is only found amongst Tibetans. It’s something precious we can be proud of and should strive to preserve.”

A portrait of His Holiness the Dalai Lama is placed at the Mahabodhi Temple in Bodh Gaya, marking the place where the Buddha attained enlightenment. His Holiness the Dalai Lama is the patron of the Tibetan Nuns Project.

Support Long-Term Stability

The annual Geshema exams and the inter-nunnery debate are both funded by endowments and are now self-sustaining thanks to our generous supporters.

We are extremely grateful to the 159 donors to the Geshema Endowment, including the Pema Chodron Foundation, the Pierre and Pamela Omidyar Fund of the Silicon Valley Community Foundation, the Frederick Family Foundation, and the Donaldson Charitable Trust. We are also very grateful to all those who sponsor nuns and help them on their path.

Now we want to put more of our core programs on a sustainable footing with our Long-Term Stability Fund. Thank you for supporting this vision. You can learn more and donate here.