Over the years we’ve published Tibetan recipes for typical dishes that the nuns eat. Now we’ve gathered all the recipes in one place for you. Our deepest thanks to Lobsang and Yolanda at YoWangdu Tibetan Culture for sharing some of their recipes and photos with us. They have many more wonderful Tibetan recipes on their website at www.yowangdu.com

Here are 5 recipes in one blog post:

Tibetan Momos

Tibetan Noodle Soup: Thenthuk

Tibetan Hot Sauce, Sepen

Dal Bhat

Vegetarian Guthuk Soup for Tibetan New Year

Recipe for Tibetan Momos

For 2 people (Makes about 25 momos)

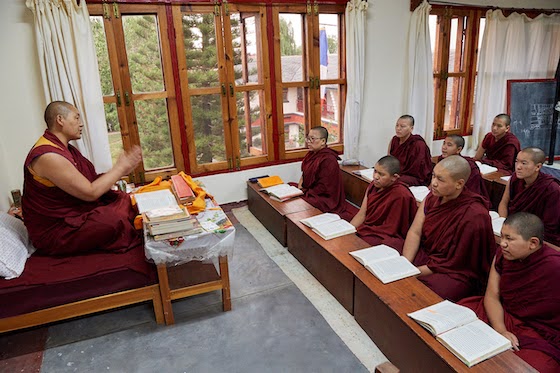

This is a vegetarian recipe for Tibetan momos or tsel momos in Tibetan. The nuns make momos for special occasions such as His Holiness the Dalai Lama’s birthday. This recipe from YoWangdu Tibetan Culture uses tofu, bok choy, and shiitake mushrooms to make momos that are light and delicious. If you don’t have time to make your own wrappers, you can buy dumpling, wonton, potsticker, or gyoza wrappers in many grocery stores. These will taste a bit different than the kind Tibetans make, but they will work.

Tibetan momos. Photo courtesy of YoWangdu.

Dough Ingredients

2 cups white all-purpose flour

3/4 cup water

Filling Ingredients for Vegetarian Momos

1/2 large onion (we use red onion)

1 and 1/2 tablespoons minced fresh ginger

4 cloves of garlic

1/2 cup minced cilantro

1 cup baby bok choy (about 2 clusters) or cabbage

5 ounces super-firm tofu

2 stalks green onion

6 largish shiitake mushrooms (you can substitute white mushrooms)

1 teaspoon salt or to taste

1 tablespoon of soy sauce

1/2 tablespoon vegetable bouillon

1/4 cup of cooking oil such as Canola

Prepare the Dough

- Mix the flour and water very well by hand; knead for about 5 minutes or until you make a smooth, flexible ball of dough.

- Leave your dough in a pot with the lid on or in a plastic bag while you prepare the rest of the ingredients. Don’t let the dough dry out or it will be hard to work with.

Prepare the Filling for Vegetarian Momos

- Chop the onion, ginger, garlic, cilantro, bok choy, tofu, green onions, and mushrooms into very small pieces.

- Heat 1/4 cup of cooking oil in a pan to high and add chopped tofu. Cook on medium high for 2 minutes, until the edges are brown (cooking all water out).

- Add chopped mushroom and cook another 3-4 minutes. Cool completely (very important) and add to filling mix.

Making the Momo Dough Circles

Making the Momo Dough Circles

- When both your dough and filling are ready, it is time for the tricky part of making the dumpling shapes. To do this, you might want to watch this video to see how to make the two traditional shapes.

- Place the dough on a chopping board and use a rolling pin to roll it out thinly, about 1/8 inch thick. It should not be so thin that you can see through it when you pick it up.

- Cutting the dough into circles: Turn a small cup or glass upside down and cut out circles about the size of your palm. Pinch the edges of each circle to thin them.

Shaping a Half-Moon Momo

- Prepare (lightly grease) a non-stick surface and get a damp cloth or lid to keep the momos you’ve made from drying out while you finish the others.

- Hold a dough circle in your left hand, slightly cupping it. Put about a tablespoon of your veggie filling in the center of the dough. Start with a small amount; try to not overfill.

- Starting on one edge and moving to the other, pinch the two sides of the dough together, creating a curved crescent shape. The bottom side of the momo will stay relatively flat, whereas the pinched edge has folds to allow for the bulk of the filling. Be sure to close all gaps so that you don’t lose juice while cooking.

Cook and Serve Your Momos!

- Boil water in a large steamer. (Tibetans often use a double-decker steamer to make many momos at one time.)

- Lightly oil the surface of the steamer.

- Once the water is boiling, place the momos a little distance apart in the steamer because they will expand a bit when they cook.

- Steam the momos for 10-12 minutes, with the water boiling continuously.

- Momos are done once the dough is cooked.

- Serve the momos right off the stove, with the dipping sauce of your choice. At home, we mix together soy sauce and Patak’s Lime Relish, which we get in Indian stores, or the Asian section of supermarkets. Tibetan hot sauce is also very good. See below for recipe!

- Be careful when you take the first bite of the hot momos since the juice is very, very hot, and can burn you easily. Enjoy!

Recipe for Thenthuk, Tibetan Noodle Soup

For 2 people

Here is a recipe for Tibetan noodle soup, called thenthuk (འཐེན་ཐུག་). This comfort food is a common noodle soup in Tibetan cuisine, especially in Amdo, Tibet. Traditionally it would be made with mutton or yak meat. Tibetan noodle soups are generally calledthukpa. Thenthuk (pronounced ten-took) is one kind of thukpa. It is easy and fun to make your own noodles.

Traditionally, thenthuk is made with meat, but the nuns follow a vegetarian diet. Thenthuk is one kind of Tibetan noodle soup and its name means “pull-noodle” soup.

Dough Ingredients

1 heaping cup all-purpose flour

1/2 cup water, room temperature

1/4 tsp salt and 1/4 tsp pepper

1 tsp oil

Soup Ingredients

2 or 3 tbsp vegetable oil

1 clove garlic, finely chopped

1 tbsp ginger, finely minced

1 small onion, chopped

1 carrot, chopped into thin strips

1 large tomato, roughly chopped

4 to 5 cups vegetable or other stock

2 green/spring onions, chopped

cilantro, a few sprigs, roughly chopped

handful of spinach

soy sauce or salt to taste

Ingredients for Tibetan noodle soup, thenthuk.

Dough Instructions

- Dough: In a bowl, combine the dough ingredients, mix well and then knead for 4 minutes.

- Cover and leave to stand for 5 minutes.

- Roll or flatten out the dough and cut into long strips and then make the broth.

Soup Instructions

- In a large pot on medium heat, sauté garlic, ginger, and onion in oil for 1 minute.

- Add carrots and tomato and gently sauté for one minute.

- Add most of the stock and bring to a boil. Adjust the amount of stock later depending on the soup to noodle ratio you prefer.

- Put the noodle in the soup by draping the strips over your hand and tearing off pieces of about an inch in size, throwing them into the boiling soup.

- Cook for 2 minutes until the noodles are cooked and the stock is boiling.

- Add the chopped green onions, cilantro, and spinach and cook for about 30 seconds.

- Season with soy sauce or salt. Serve immediately.

Recipe for Tibetan Hot Sauce

Tibetan hot sauce, called sepen in Tibetan, is a popular accompaniment to Tibetan momos and other dishes. While the nuns hand chop all their ingredients, you can make this recipe with a food processor or blender. Add this spicy sauce to anything you like, but be careful, this sepen is extremely hot! You can adjust the heat of the sauce by reducing the amount of red pepper.

Ingredients for Tibetan Hot Sauce

1 medium onion

2 medium tomatoes (Roma tomatoes work well)

2 tablespoons cilantro

chopped 2 stalks of green onion

2 stalks of celery

3 cloves garlic

½ teaspoon salt

1 cup dried red peppers (see the note below)

1 tablespoon vegetable oil for cooking

NOTE: You can adjust the spiciness of this recipe by using less red pepper and/or more of the other ingredients.

Instructions

- Roughly chop the celery, tomatoes, green onion, and cilantro.

- Peel and roughly chop garlic.

- Peel and cut onion in half lengthwise, then slice fairly thin.

- Slice tomato in thinnish circles.

- Heat oil in pan on high.

- On high heat, cook garlic a few seconds, then add onion slices and stir fry about 1 minute.

- Add celery and whole red peppers, stir fry another minute.

- Add tomato slices, and stir fry for a minute or so.

- Stir in cilantro, chopped spring onion, and salt.

- Cover and cook for about 3 minutes.

At this point, everything should be cooked down a bit. Put everything in a blender or food processor until you have a sauce. Stop at the thickness you like.

Recipe for Dal Bhat

Serves 2 people

Traditionally Tibetans in Tibet don’t cook dal, but it is a very common dish among Tibetans in exile, especially those in India and Nepal. Dal bhat is a traditional Nepali or Indian food consisting of lentil soup (dal) served with rice (bhat). Here’s a recipe from Yowangdu Tibetan Culture for how to cook Tibetan-style dal (or dal bhat). This recipe has been slightly edited for length.

Ingredients

1 cup red lentils (masoor dal) (other types of dal can take much longer to cook)

1 tablespoon vegetable oil

1 small red onion, chopped small

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon ginger, minced

¾ teaspoon salt

½ teaspoon mustard seeds

½ teaspoon turmeric*

½ teaspoon cumin seeds*

½ teaspoon coriander powder*

1 medium tomato, diced

½ tablespoon butter or ghee (optional, but it gives a nice flavor)

2 tablespoons cilantro and/or green onion, chopped, for garnish

water, to make soup

basmati rice (or any kind you wish)

Indian chutney or pickle (achar) of your choice. Patak’s lime pickle and other pickles can be found at many large grocery stores.

Optional: add pepper of your choice, or red pepper flakes.

*If you prefer, you can use Shan Dal Curry Mix or garam masala instead of the turmeric, cumin and coriander.

Instructions

- Wash the lentils and rinse a couple of times. Be careful to remove any stones. If you have time, soak the lentils in water as long as you can, up to overnight, before you cook. They get very soft and can cook faster.

- Begin preparing the rice any way you like so it will be ready when you’re done cooking the dal.

- Chop your onion, and mince the garlic and ginger and set aside.

- Chop the tomato and set aside.

- Wash your cilantro and or green onion. Chop for garnish and set aside.

- Heat oil on high for a minute or two.

- Add ginger, garlic and onion, and stir fry on high until the onion is a little brown on the edges, 1-2 minutes.

- Stir in cumin seeds, salt, turmeric, mustard seed and coriander powder. Turn the heat down to medium (6 out of 10 on our stove), and cook for 2 minutes, stirring often. Keep the stove at medium (6/10) for the rest of the cooking process and stir occasionally.

- Add tomatoes and butter. Stir, cover with lid and cook for 4 minutes.

- After 4 minutes, stir in the lentils, cover and cook for 5 minutes.

- After cooking for 5 minutes, add one cup of water, cover with lid and cook for 5 more minutes.

- When the 5 minutes are up, stir in 2 more cups of water, as the water will begin to decrease as you cook.

- Continue cooking on medium for 10 minutes.

- Now your dal is ready. Turn off the stove and sprinkle the chopped cilantro and/or green onion on top.

- Serve with rice.

NOTE: Many Tibetans like to serve the dal in a small soup bowl, beside a plate of rice. Some people like to ladle the dal over the rice and mix it up to eat. Indians and Nepalis often eat dal baht with their hands, as do some Tibetans, but many of us also use a spoon.

Add some Indian chutney or pickle (achar) or hot sauce such as Patak’s Lime Pickle or relish, which is goes very well with this dal bhat.

Recipe for Tibetan Guthuk

Serves 2 or 3 people depending on your appetite.

Double or triple this for a guthuk party.

This is a recipe for Losar or Tibetan New Year. Guthuk is a special soup is eaten on the night of the 29th day of the 12th month, or the eve of Losar. Guthuk is the only Tibetan food that is eaten only once a year as part of a ritual of dispelling any negativities of the old year and to make way for an auspicious new one.

Vegetarian guthuk soup. Photo and recipe courtesy of YoWangdu.com

Guthuk gets its name from the Tibetan word gu meaning nine and thuk which refers generally to noodle soups, so guthuk is the soup eaten on the 29th day. The gu part of the name also comes from the fact that the soup traditionally has at least nine ingredients. In this vegetarian version of guthuk, the nine main ingredients are mushrooms, celery, labu (daikon radish), peas, tomato, onion, ginger, garlic, and spinach. A traditional guthuk would include meat (yak or beef) and dried cheese.

This guthuk recipe from YoWangdu is a fusion of traditional and contemporary Tibetan cooking. It has a traditional Tibetan noodle soup called thukpa bhatuk as its base, but is vegetarian and includes celery and mushrooms for a flavorful vegetarian broth.

What makes the soup extra special is that each person eating the soup receives one large dough ball with a hidden surprise inside it. Tucked inside the dough ball is a item or symbol of that item which is meant to be a playful commentary on the character of the person who gets it.

Guthuk dough ball with the Tibetan word for salt inside it. Photo © YoWangdu

In the dough ball above, for example, is a slip of paper with the Tibetan word for salt (tsal). This is supposed to symbolize a lazy person. Traditionally, there would be an actual piece of rock salt inside the dough ball. In any case you don’t want to draw the dough ball with salt!

The objects or words placed into each large dough ball are jokingly meant to refer to the character of the person who gets it. Here’s a list of four positive and six negative objects and their Tibetan words and symbols:

Wool (bay) means you’re kind hearted

A thread rolled inwards (kuba nandrim) symbolizes a person who draws luck and money

Sun (nyima) means the goodness related to light

Moon (dawa) also means the goodness related to light

Chili (sepen) means a sharp tongue

Salt (tsa) means you’re lazy

Glass (karyul) symbolizes someone who is happy when there’s fun, but disappears when there is work to do

Coal (sola) means you’re black hearted

A thread rolled outward (kuba chidrim) represents someone who spends or dissipates luck or money

A small prickly ball (semarango) symbolizes a prickly person

A nice Tibetan custom is that, if any family member is absent, he or she still gets a bowl of guthuk served up, with the extra dough ball, and someone will call them to tell them what object they got.

Vegetarian Losar Guthuk Ingredients. Photo © YoWangdu.

Dough Ingredients for Guthuk

1 and 1/2 cups all-purpose white flour

1/2 cup plus 2 tablespoons water

Soup Ingredients

2 cloves garlic, minced

1 tablespoon ginger, minced

1/3 medium onion

5 medium shiitake mushrooms

1 tomato, chopped

2 stalks of celery, chopped

3 teaspoons low-sodium soy sauce (if using regular soy sauce, leave out the salt)

1 teaspoon salt

3 cups water (first cooking) + 3 cups of water (second cooking)

1/3 cup raw sugar snap peas, without shells

2/3 of a large labu, cut into strips, see instructions below. (labu = daikon = Japanese radish)

5 cups spinach (measure before chopping), roughly chopped. (As long as they are clean, no need to remove the stems.)

1 stalk green onion, chopped

1 cup cilantro, chopped

Instructions for Guthuk

- Prepare the soup Ingredients. First mince the garlic and ginger.

- Chop the onion.

- Roughly chop the celery, mushrooms, and tomato.

- Prepare the labu (daikon radish) by peeling it with a potato peeler, removing the two ends, and chopping it into thin, narrow strips about as long as your finger. Soak the chopped labu in water with about 1 tsp of salt; swish around and leave for several minutes before draining and rinsing well several times to remove the saltiness and bitterness. Tibetans say that rinsing like this gets rid of the strong radish smell.

- Chop the garnishes.

- Finely chop the cilantro.

- Chop the green onion.

- Roughly chop the spinach (or don’t chop if you like large pieces)

- Set all these aside until the soup is almost done.

- Prepare the dough by slowly adding the water to the flour.

- Mix the flour and water to form a ball and then knead for a couple of minutes. The dough will be a bit dryish and stiff. If you can’t form a ball, you can a little more water. If dough is sticky, add a tiny bit more flour. This dough does not have to rest after kneading so you can prepare it any time during the cooking process.

- Shape the dough. From this dough, you will make two different types of things – first are the bhatsa, which are the normal little gnocchi-like scoops of noodle in an everyday thukpa bhathuk, and second are the large round dough balls (one for each person eating the soup) that contain hidden items or messages which is what makes this soup a guthuk.

Making the dough rope for the bhatsa in guthuk. Photo © YoWangdu

Making the Normal Bhatsa Noodles

Pinching off dough and pressing the bhatsa for guthuk. Photo © YoWangdu.

- First, rub the ball of dough between your hands to make it into a thick tube of dough, and then pinch off pieces of that tube to make 4-5 chunks of dough.

- Then rub each piece of dough between your hands to form long, thin ropes of dough.

- Pinch off a piece as big as the end of your fingernail, or smaller.

- Rub the dough with one finger in the palm of your hand to cause the little piece of dough to curl up (the better to scoop up the juices in the soup). These little scooped pieces of dough are your bhatsa.

- Repeat until you’ve used up all but 1 of your ropes of dough.

- You can sprinkle a little flour around the pile of bhatsa, to keep them from sticking together.

Making the Special Dough Balls with the Hidden Items or Messages

- Pinch off a piece of dough 4-5 times as big as one of the normal bhatsa. Basically, the dough balls need to be easily distinguishable in the soup, so that we can pick out our dough ball from among the bhatsa.

- Roll it roughly into a circle between your hands, but before you finish rolling it, fold one of the pieces of papers with the special messages, and stuff it into the center of the dough ball, then re-roll it to make the ball as smooth as you can. It’s best if there are no cracks so that paper stays dry inside the dough ball when we cook it. Of course if you wish, you can add the actual items, like some salt, or coal, inside the dough ball. But these days most people outside Tibet just put a paper with a word or symbol written on it to signify the item.

- Make one dough ball for each person eating your guthuk.

Cook the Soup

- Lightly brown the ginger, garlic and onion on medium high, about 3 minutes.

- Add celery, mushrooms, tomato, soy sauce and salt and cook on high for about 7 minutes.

- Add 3 cups of water, keeping heat on high, and bring to a boil.

- When the broth starts to boil, turn down to low and simmer for 10 minutes

- After the broth has simmered for 10 minutes, add 3 more cups of water, turn heat on high and bring broth to a boil.

- After the broth begins to boil, add the prepared labu and green peas. Heat remains on high.

- After 5 minutes, add the bhatsa and the large guthuk dough balls with the special messages inside them. Heat remains on high.

- When cooked the bhatsa noodles and the large dough balls will pop up to the surface of the soup. This will take about 5 minutes. When most of them are popped up to the surface, turn off the heat but leave on the burner.

- Stir in spinach, cilantro, and green onion and serve right away. (These final ingredients do not really need to cook, and look nicer if they are fresh looking.)

- Put one big dough ball in each bowl of soup.

- Serve right away – it is best to eat hot!

- After you have enjoyed the soup for a while, each person can fish out his or her dough ball and dig out the message inside for some fun!

It is traditional that everyone saves a bit of their soup and then dumps it into a communal dish with a little dough effigy. Place a candle in the dish and carry whole thing out of the house being careful not to look back at the house. Take it to the nearest intersection so that the bad spirits now attached to it will get confused and not return to the home.

Making the Momo Dough Circles

Making the Momo Dough Circles